There are two different kinds of diabetes. It’s important to know the symptoms associated with each one. Here’s a straightforward definition of the two different types from Bob Greene’s The Best Life Guide to Managing Diabetes.

There are two different kinds of diabetes. It’s important to know the symptoms associated with each one. Here’s a straightforward definition of the two different types from Bob Greene’s The Best Life Guide to Managing Diabetes.

Type 1 Diabetes

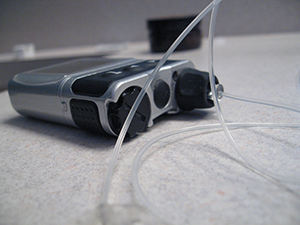

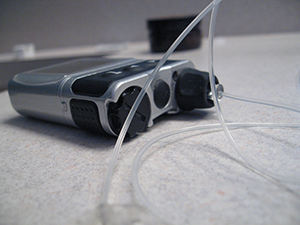

If you have diabetes mellitus type 1, you’ll need to take insulin, because with this type of diabetes, the body makes essentially no insulin at all. (People are often making some insulin when first diagnosed, but in nearly all cases it eventually dwindles down to virtually nothing. Sometimes it happens because the pancreas, where insulin is made, is removed surgically or severely damaged by a disease such as pancreatitis. But by far the majority of type 1 cases are triggered by an autoimmune disease that destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. (An autoimmune disease occurs when a person’s immune system attacks normal body tissue instead of protecting it. That’s what happens in rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and some forms of thyroid disease, for example). Experts aren’t really sure what triggers autoimmune disorders. Many believe the most plausible theory is that a person is first hit with a virus, but instead of just fighting off the virus, the immune system starts attacking organs, such as the pancreas in the case of diabetes.

Unfortunately, even after the virus has been completely destroyed, the immune response continues to damage the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Whether the virus theory pans out or whether other forces, such as environmental toxins or genes that go awry, are at play, the end result is clear: over time, most or all of the beta cells are destroyed and insulin production dries up. This causes type 1 diabetes.

The process of autoimmune damage to the body’s insulin-producing cells usually takes years, and most people aren’t even aware when it begins. It typically progresses to the point of diabetes sometime in childhood or adolescence. For this reason, diabetes mellitus type 1 used to be called juvenile diabetes. This term is still commonly used, but many people develop type 1 diabetes in their 30s, 40s, or even later, so this isn’t really an accurate description. The term insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus or IDDM was also used in the past, but this really isn’t an accurate term either, because many people with type 2 diabetes also need insulin.

It’s easy to make the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes when a young child has high blood sugar, but it’s not always easy to know whether an older adolescent or adult has it or whether it is type 2. The distinction is critical because the doctor needs to know whether to start insulin treatment — mandatory for type 1 — or whether it is safe to try oral medication first. Sometimes blood tests such as the C-peptide test, which can tell whether the person is making any insulin, or tests for antibodies that are part of the immune attack against the pancreas, are helpful. But often the diagnosis becomes clear only over time, such as when a person fails to respond to oral medications.

Genetics can play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes, and in some cases you’ll find a family with many members who have the condition, but that’s not usually the case. It’s the thought that some people inherit a genetic susceptibility to something in the environment, such as a particular viral infection, which can trigger the autoimmune reaction. If they don’t get the virus, that autoimmune reaction will never spring to life. Currently, there are no genetic tests that will reliably tell you if you’re likely to develop type 1 diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes accounts for 5 to 10 percent of all people with the condition. There is some evidence that the incidence of type 1 diabetes may be increasing, but it still represents only a minority of cases. And even if it is increasing, it is doing so at a much slower rate than the other major form: diabetes mellitus type 2.

Type 2 Diabetes

Those headline-grabbing statistics — the 90 percent rise in diabetes prevalence in the last decade and the tripling of diabetes cases since the 1980s — are all about type 2 diabetes. And the staggering number of people with pre-diabetes doesn’t bode well for an end to the epidemic. Type 2 diabetes makes up to 90 to 95 percent of all diabetes cases. It used to be known as adult-onset diabetes — not anymore; it has begun to strike children and adolescents at an alarming rate. Even though the prevalence is still much lower in young people than in the adult population, it has increased by 33 percent in the past fifteen years, especially among certain racial and ethnic groups, such as African-Americans, American Indians, Hispanic/Latin Americans, and some Asian and Pacific Islanders. Type 2 diabetes also used to be called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus or NIDDM, but this is misleading as well because many people with type 2 need insulin treatment.

Type 2 diabetes is actually a bit more complicated than type 1. In type 2, both a deficiency of insulin and the body’s lackluster response to insulin, known as insulin resistance, are at work. Let’s focus on insulin resistance for a moment.

Earlier on, we compared insulin to a doorman in a fancy building. Well, if the door is stuck, even the doorman can’t get it open. That’s what happens when a person develops insulin resistance. The glucose is there, waiting to get into the cell, but insulin can’t open the door. Now, if the doorman gets a couple of his buddies, all of them together might be able to open the door. It’s the same thing in insulin resistance. Insulin resistance means that it takes a lot more insulin to do the job than in a normal situation.

That’s exactly what your body does early on in the disease: your pancreas spews out high levels of insulin to normalize your blood sugar level. After a while, though, your body can’t make enough insulin to corral all the glucose, and your blood sugar rises into the diabetic range. No one is sure why this happens. Some decline in insulin production is natural with aging, and it may be that the pancreas eventually just gets “worn out” from putting out all that extra insulin. Once the blood sugar level rises, the problem gets worse. High glucose levels further damage the pancreas’s beta cells, a phenomenon called glucose toxicity, and insulin production plunges further. So, while most people with type 2 diabetes start out with insulin resistance, most also develop insulin deficiency as time goes on.

By Bob Greene

Share Your Comments & Feedback: